About the Monarch Butterfly:

The monarch butterfly (Daneus plexippus) is the most iconic butterfly in North America: its flashy orange and black wings and expansive migration and breeding grounds make it easily recognizable across the continent.

In addition to its scientific and environmental value, the monarch has huge cultural significance to people across Canada, the United States, and Mexico. While monarchs are native to all areas of North America and have been introduced to Hawaii, the Caribbean, Australia, and some areas of Europe, the concern of this document is primarily for the famed eastern migratory subpopulation of monarchs, with habitat ranging from the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains to the east coast.

Members of the eastern monarch population are seen in New Jersey in the summer months, and can be observed in Cape May each year as they begin their epic fall migration to wintering roosts in central Mexico.

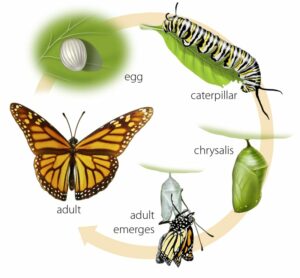

Life Cycle:

It is important to distinguish between the spring and summer breeding monarchs and the generation that makes the phenomenal fall migration. It takes four to five generations of monarchs to complete the annual cycle of migration and breeding.

For non-migratory monarch generations:

An average monarch butterfly in summer breeding grounds will complete its lifecycle in six to eight weeks. A female monarch ready to lay eggs must seek out milkweed (Asclepias), as it is the only host plant that can support monarch caterpillars. There are about 140 recorded species of milkweed, many of which are widespread in different areas of the monarch’s breeding range and play an integral role in successfully rearing the next generation of monarchs. Once an egg is laid on a milkweed leaf, it will develop for three to five days before hatching into a caterpillar.

For 10 to 14 days, the monarch caterpillar will grow. Aside from the initial task of eating its eggshell and the occasional snack of the molten skin it has outgrown, the caterpillar subsists solely on milkweed leaves.

Once the monarch has completed its two-week phase of growing, molting, and eating, it will enter the pupal stage. The monarch will remain in the pupal stage for 10 to 14 days as it develops into an adult monarch butterfly.

Once the monarch emerges from its chrysalis, its wings dry and harden, and it will begin its life as an adult butterfly. The adult monarch will reach sexual maturity within four to five days of emerging from its chrysalis, and reproduce shortly thereafter to complete its life cycle.

For the migratory monarch generation:

The migratory monarch generation is very different from the non-migratory generations that precede it in the annual cycle; after completing the first three phases of their life cycle—egg, caterpillar, and pupa—as normal, they enter a phase called “diapause” which causes them to be physiologically distinct from previous generations. Diapause refers specifically to the prolonged state of sexual immaturity of the butterflies, where neither the males nor females are sexually developed enough for reproduction.

This generation of monarchs can live for about eight months, compared to the much shorter lifespan of an average breeding monarch. This expanded lifespan will allow the monarch to migrate all the way to its wintering roosts in Mexico — some coming from as far away as southern Canada — and then to migrate again after winter’s end, with most making it as far as Texas and the Gulf States before coming to rest at their new breeding grounds.

This generation of monarchs will not reach sexual maturity until the winter is over, upon which they will begin their northerly trek back into the United States. When they reach the breeding grounds in Texas and the Gulf States, they will finally reproduce and complete their life cycle.

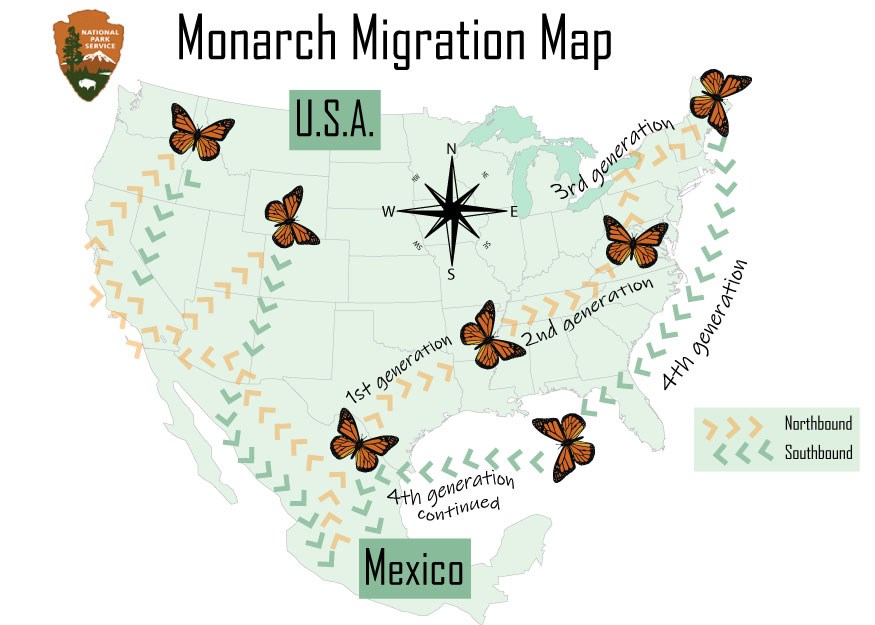

Migration

Monarchs have a very distinct and fascinating migration pattern. The annual cycle of eastern migration begins with the fall migration, during which monarchs on the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains — from southern Canada to the U.S. Midwest –follow different paths to the wintering sites they return to year after year.

The western population overwinters primarily in coastal California, with some heading south towards Mexico. During the migration, monarchs need to rest and refuel at “stopover” sites along the flyway. Cape May, New Jersey is one such site where the butterflies can be seen congregating each year.

The fall migration is complete once the monarchs reach their overwintering sites. While each migrating flock is at least 4 generations removed from the previous generation to make the flight, they find these sites consistently through each cycle. There is evidence that the butterflies have a biological compass guided by sunlight to steer them towards Mexico, but how they find the exact sites of the sanctuaries remains a mystery.

Why are Monarch Butterflies important to our environment?

The annual migration of the monarch butterfly through New Jersey is a much anticipated phenomenon, one that holds environmental, educational, and economic value to the state.

Monarch butterflies are among the group of native pollinators that aid in the successful reproduction of many key fruit and vegetable crops across the state, and are crucial to New Jersey’s agricultural and economic success. Monarchs are also an indicator species for environmental health: monarch health often reflects the overall health of the environment.

Yet the monarch butterfly is facing severe decline, with the unique and fascinating migration of the eastern monarchs through New Jersey each fall having dwindled.

It is imperative to preserve pollinators for the sake of food security, and the security of the environment as a whole. Monarchs and other butterflies are sensitive to environmental changes, and their decline serves as a readily visible sign of the condition of the environment for other living things as well.

Efforts to aid monarch recovery concurrently benefit species at all levels of the ecosystem. Monarchs and other insects are near the base of an ecosystem’s food chain; they respond strongly to fluctuation in available food (plants), and the high visibility of butterflies translates the changes in plant life into something humans will notice.

Their placement in the overall food chain also means that other animals that rely on monarchs and other insects for food are affected by their population decline, and by efforts to aid them.

Population Decline:

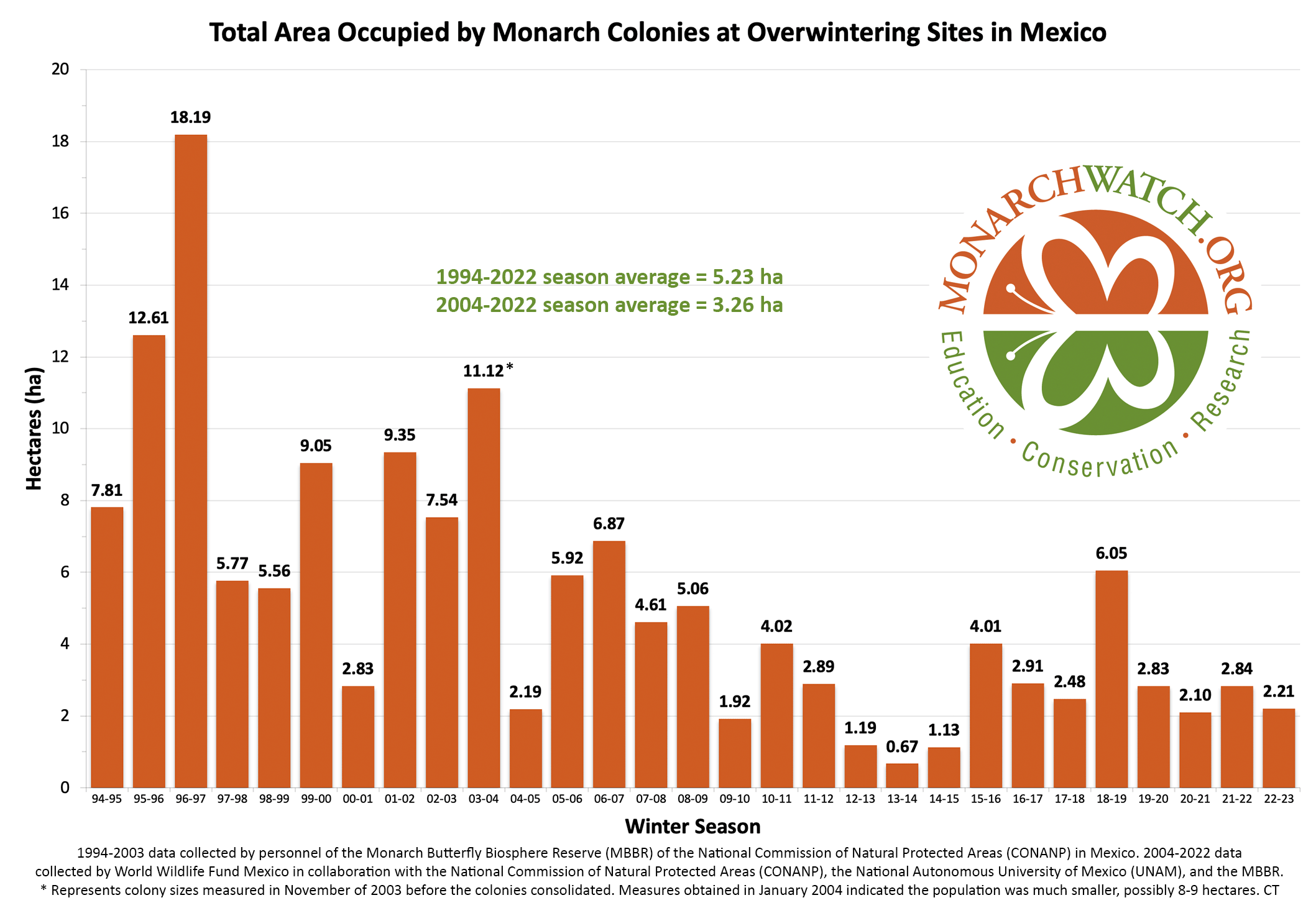

Over the past several decades, the number of monarch butterflies in North America has steeply declined. The great migration of the eastern monarchs has been named a “threatened phenomenon” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). As of a 2014 estimate, the monarch population has declined some 90% since 1990, from approximately one billion butterflies to 35 million butterflies.

Monarchs are very sensitive to temperature change and weather conditions; changes in climate affect both the overall climatic suitability of habitat and the frequency and severity of extreme weather events in the monarchs’ broad habitat range. The changing climate may shift the availability of summer breeding habitat and disturb the even more fragile microclimate of the monarchs’ overwintering sanctuaries in Mexico.

The increased use of herbicide tolerant (HT) crops has been an issue for the monarch caterpillar’s only host plant, milkweed. Much of the corn and soybean crops grown in the U.S. are now genetically modified to be resistant to glyphosate, a synthetic systemic herbicide used against perennial weeds. The glyphosate-resistant nature of the crops allows for broad spraying of the herbicide over fields, eliminating all plant life without that resistance that may otherwise compete with the crops for nutrients, sunlight, and other resources.

Unfortunately, milkweed cannot withstand glyphosate spraying, and thus the milkweed that previously thrived in farm fields is rapidly disappearing.

Monarchs are losing milkweed and native nectar plants not just in agricultural fields and surrounding areas, but also even relatively chemical-free areas that are being overtaken by destructive introduced species that may not be usable to monarchs and other butterflies for food or other survival needs.

Camden County Efforts

There are many well-established and emerging efforts to conserve and protect the monarch butterfly, though additional support is greatly needed within our communities.

Camden County has been focusing on the importance of the Monarch Butterfly to our many environments and striving for preservation and growth of the Monarch community.

What we’ve accomplished:

- Monarch Waystations (gardens with both milkweed plants and nectar plants) have been installed at the Lakeland Complex as well as the Parks Department.

- Educational events aimed to educate residents of Monarch butterfly biology and importance of waystations have been conducted for both adults and children where we supplied attendees with milkweed plants and coneflower seeds (nectar plants) necessary to begin installation of waystations.

What we have planned to do:

- Another educational event is scheduled for August 22 at the Parks Department. This event includes the release of 100 adult monarch butterflies and milkweed plant giveaways.

- Monarch Waystations are in the process of installation at our County Parks with the intention of certification by the Monarch Watch.

View & Download the PDFs below for more information on Monarch Butterflies and Pollinators:

- Creating Pollinator & Native Plant Gardens

- Monarch Waystations

- Monarch Migration

- Pollinator Friendly Practices

- Pollinators & Native Plants

- Pollinators, Plants, People